First generation HDMI 1.4 spec UHD 4K, next-generation HDMI 2.0 spec UHD 4K and what integrators need to know.

An analysis of 4K Interim vs 4K Proper by Chris Pinder, Founder and MD of HDanywhere, June 2015.

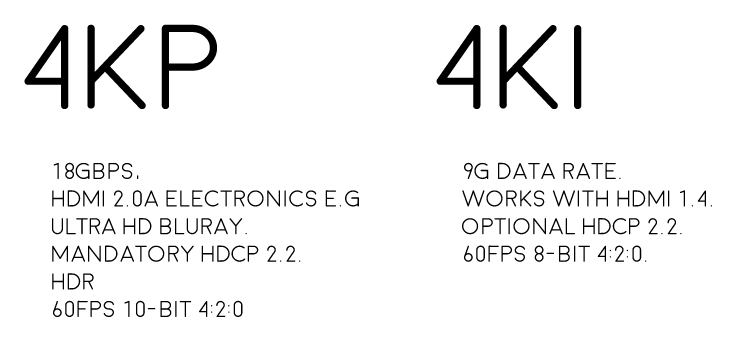

4K is a complicated subject matter. 4K isn’t one format, it’s an umbrella term for many combinations of resolutions, frame rates and colours. Talking about 4K in too generalised a way is dangerous. When I discuss 4K with anyone, in as non-patronising a way as possible to simplify and aid understanding, I refer to ‘i’ and ‘p’, (like 1080i and 1080p) but my ‘i’ and ‘p’ doesn’t mean interlaced and progressive, I mean first generation 4K and next-generation 4K, or in other words ’interim’ and ‘proper’. P could also quite easily stand for ‘premium’.

This is my take on the two-speed world of 4K UHD devices at the moment. It may be labelled and marketed as 4K, it may even support HDCP 2.2 – but is it 4Ki or 4Kp?

Proper 4K (4Kp) is next-generation HDMI 2.0 spec 4K, it’s what Ultra HD Blu-ray is and what premium 4K content will be. Ultra HD video refreshes at a smooth 60 frames per second in amazing 10-bit 4:2:0 colour (or if your display doesn’t support 10-bit) 8-bit 4:4:4 colour – basically hugely superior colours than what we have seen before over HDMI. 4Kp can also support HDR content and runs at very high 18Gbps data rates and, as a result, will require all new high-bandwidth HDMI 2.0a* spec electronics. 4Kp will also have HDCP 2.2 copy protection encrypting the content, which I’ll touch on later.

What is most important from integrator perspective is that single-cable HDBaseT DOES NOT carry 4Kp. It will only carry 4Ki because HDBaseT is max 10.2Gbps and 4Kp requires 18Gbps.

Most devices out there today labelled as ’4K’ do not support 4Kp, they only support 4Ki. And by most, I mean over 95%. But this is improving, more and more displays are coming out now that support HDMI 2.0 and have a 10-bit panel. Ultra HD Blu-ray is likely going to be the first 4Kp source device we see. So what is 4Ki?

Interim 4K (4Ki) runs at a 9G data rate (half that of 4Kp) and doesn’t necessarily require new HDMI 2.0 electronics. It will work on older HDMI 1.4 spec devices. It may or may not have HDCP 2.2 encryption. And colour-wise if it’s running at 60fps it can only be the lesser 8-bit 4:2:0 quarter colours. For 4:4:4 a lower 30fps refresh rate is used instead and smooth panning shots are sacrificed. 10-bit colour content just flatly isn’t supported full stop.

What is so important about colours?

4Kp/60 and 4Ki/60 if watched in black and white are EXACTLY the same. The same number of pixels wide and high, refreshing at 60 times per second, with the same pixel data for light and dark contrast. So no difference in sharpness, motion or contrast.

Where they differ is with a compromise on colour. The resolution of the colour layer that gets laid over the top of the black and white frame when combined to make the final image. With 8-bit 4:4:4 each pixel can choose a colour, whereas with 4:2:0 every 4 pixels have to share a single colour choice. Even though a cluster 4 pixels are sharing the same colour, the overlay of the black and white image creates different shades. The resulting 4:2:0 video content, although a lesser quality, is not as substantially different from 4:4:4 as you might think. In fact, when viewing the two from a couple of metres away, the human eye really struggles to differentiate them.

OK, now that you’re thinking is in tune with there being two primary types of 4K material and you understand the difference between the two.

You also NEED to be aware of a couple of associated meteors about to hit the AV side of the CI industry that relate to the facilitation of working 4K HDMI systems. (Remember HDMI is a system, NOT a cable) One is called ‘HDMI 2.0′ and the other is ‘HDCP 2.2′. The two meteors should really hit simultaneously, but not necessarily.

Meteor 1: HDMI 2.0 is the new twice-as-big digital pipeline to accommodate the higher data rates of proper 4K jumping from 9G to 18G bandwidth. Its not a new cable design, its new electronics at either end of the existing (short) HDMI cable we use. So that is new source devices (Ultra HD Blu-ray players for example) and new displays (10-bit SUHD Samsung panels for example). However for longish cable distances, say 3m and over, current passive cables may struggle with the higher data rates. We’ll begin to see some new breeds of HDMI cable types appear to solve this. Some will use integrated active/powered boosting chips and others are likely to be a copper/fibre hybrid cable. Existing long length HDMI cables, that may be buried in walls for example will be able to be utilised through the use of restorative dongles that can be placed at the start and end of the cable run. I expect to see this HDMI cable rescue/fixer market grow over the coming years sharply.

Meteor 2: HDCP 2.2 is the new 128 bit encryption designed to secure 4K content from being pirated. It is the same level of security encryption as credit card issuers use for internet transactions. Unless every device in the signal path is HDCP 2.2-capable, theoretically the content will not be shown. Source, matrix, AVR, balun, display, projector must all support HDCP 2.2. One weak link means black screen. The thing about HDCP 2.2 support is that it’s essential to ensure the best chance of displaying 4K content from your favourite content providers (i.e Hollywood and sports). The HDCP 2.2 event horizon will largely be determined by the release of Ultra-HD 4K Blu-ray and 4K content being delivered via our set-top-boxes.

Conclusion

In summary, until more next-gen 4Kp source devices, like Ultra HD Blu-ray, set-top-boxes, and media players are released we live in a kind of interim 4K limbo land, a phoney, interim 4K world with no proper, premium 4K content to enjoy. In addition to this, more displays with HDMI 2.0, HDCP 2.2 and 10-bit panels need to be released so that users can take full advantage of the advancements in picture quality offered by 4Kp. Month-on-month this situation improves.

From an integrator perspective, quite rightly there is a lot of emphasis currently on HDCP 2.2 support within matrixes. But even when HDCP 2.2 compliant, single-cable HDBaseT is a bottleneck in many video distribution systems, which will result in premium 4K content video quality being downgraded when distributed. There is a quality compromise currently in order to deliver a distributed solution over a single network cable.

SIDELINE RED HERRING: What about 4K streaming like Netflix?

Well it’s not 4Kp and it’s not 4Ki… It’s dynamically compressed, streamed 4K content using AVC H.264 and HEVC H.265 codecs with varying quality from home to home according primarily to the speed and quality of their network. For the purposes of this article, I am talking about uncompressed 4K content.

More info here: http://www.dailytech.com/Netflix+to+Stream+House+of+Cards+in+4K+via+HEVC+H265+Compression/article33962.htm